Collaborative Multi-Robot

Non-Prehensile Manipulation via Flow-Matching Co-Generation

Yorai Shaoul, Zhe Chen*, Naveed Gul Mohamed*,

Federico Pecora, Maxim Likhachev, and Jiaoyang Li.

Our Goal

Explore multi-robot collaboration.

Collaboration is:

Collaboration

Robots work together, and depend on each other, to complete a global task.

Collaboration is not:

Coordination

Robots execute learned behaviors in a shared

environment to complete private tasks.

The Collaborative Manipulation Problem

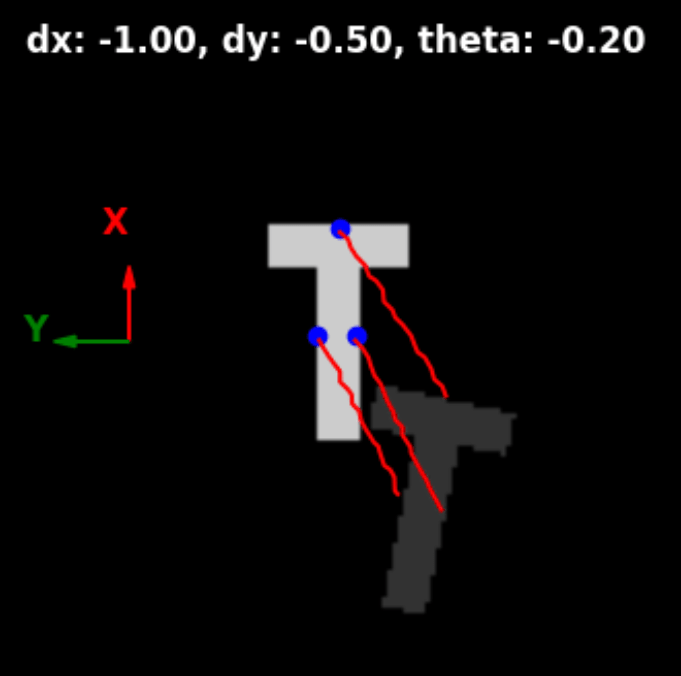

Given

- a set of \(N\) robots \(\mathcal{R} := \{\mathcal{R}_i\}_{i=1}^N\),

- observations of movable objects

\(\mathcal{O} := \{\mathcal{O}_j\}\), \(\mathcal{I}(\mathcal{O}_j) \in \mathbb{R}^{W\times W}\), - Poses and shapes of obstacles,

- Target poses for all objects.

The Collaborative Manipulation Problem

Given

- a set of \(N\) robots \(\mathcal{R} := \{\mathcal{R}_i\}_{i=1}^N\),

- observations of movable objects

\(\mathcal{O} := \{\mathcal{O}_j\}\), \(\mathcal{I}(\mathcal{O}_j) \in \mathbb{R}^{W\times W}\), - Poses and shapes of obstacles,

- Target poses for all objects.

We want to

Compute a set of motions \(\Tau := \{\tau^i\}_{i=1}^N \) such that, upon execution, all objects arrive at their goals.

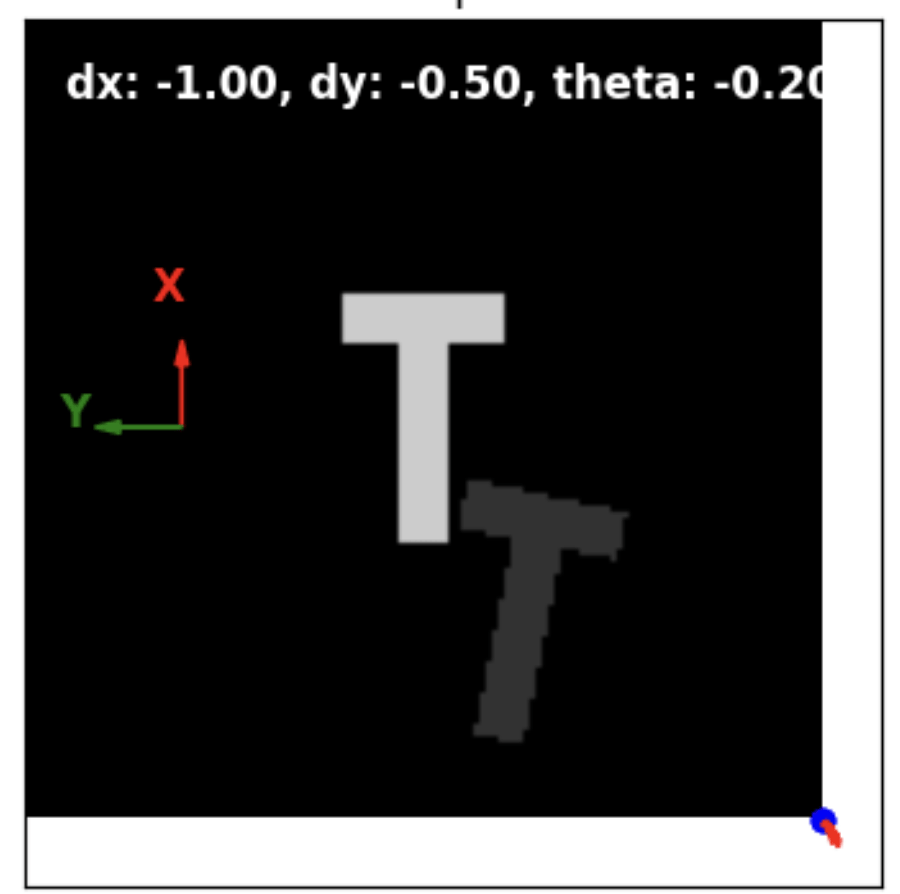

The online problem

Compute short-horizon motions \(\Tau := \{\tau^i\}_{i=1}^N \), execute them, and repeat. Eventually, the objects must arrive at their goals.

Planning and Learning For Collaboration

Our approach: learn what we "must," and plan what we can.

Let's directly describe our framework:

- Observe objects.

- Plan object transformations.

- Generate manipulation interactions.

- Plan robot trajectories.

- Execute and repeat.

Planning and Learning For Collaboration

Planning and Learning For Collaboration

Our approach: learn what we "must," and plan what we can.

Let's directly describe our framework:

- Observe objects.

- Plan object transformations.

- Generate manipulation interactions.

- Plan robot trajectories.

- Execute and repeat.

Planning and Learning For Collaboration

Planning and Learning For Collaboration

Our approach: learn what we "must," and plan what we can.

Let's directly describe our framework:

- Observe objects.

- Plan object transformations.

- Generate manipulation interactions.

- Plan robot trajectories.

- Execute and repeat.

Planning and Learning For Collaboration

Planning and Learning For Collaboration

Our approach: learn what we "must," and plan what we can.

Let's directly describe our framework:

- Observe objects.

- Plan object transformations.

- Generate manipulation interactions.

- Plan robot trajectories.

- Execute and repeat.

Planning and Learning For Collaboration

Planning and Learning For Collaboration

Our approach: learn what we "must," and plan what we can.

We do so with the following procedure:

- Observe objects.

- Plan object transformations.

- Generate manipulation interactions.

- Plan robot trajectories.

- Execute and repeat.

Planning and Learning For Collaboration

Planning and Learning For Collaboration

Plan motions

to contact points

Learn short

push trajectories

Plan motions

for objects

Planning and Learning For Collaboration

We interleave plannning and learning in a generative collaboration framework \(\text{GC}\scriptsize{\text{O}}\).

Agenda

- We'll start by looking at learning manipulation interactions,

- Continue to our multi-robot planning algorithm \(\text{G}\scriptsize{\text{SPI}}\)

Plan motions

to contact points

Learn short

push trajectories

Plan motions

for objects

Planning and Learning For Collaboration

Learning Multi-Robot Manipulation

We seek to learn two things:

- Manipulation trajectories

- Contact points

In this work, we do so jointly with imitation learning.

Learning Multi-Robot Manipulation

We seek to learn two things:

- Manipulation trajectories

- Contact points

Learning Multi-Robot Manipulation

We seek to learn two things:

- Manipulation trajectories

- Contact points

Learning Multi-Robot Manipulation

We seek to learn two things:

- Manipulation trajectories

- Contact points

Learning Multi-Robot Manipulation

We seek to learn two things:

- Manipulation trajectories

- Contact points

Learning Multi-Robot Manipulation

Many manipulation trajectories and contact points

combinations are valid, but not all are useful.

Learning Multi-Robot Manipulation

Many manipulation trajectories and contact points

combinations are valid, but not all are useful.

Learning Multi-Robot Manipulation

Many manipulation trajectories and contact points

combinations are valid, but not all are useful.

Learning Multi-Robot Manipulation

Difficult to generate.

Need to reason over manipulation dynamics and contact formations.

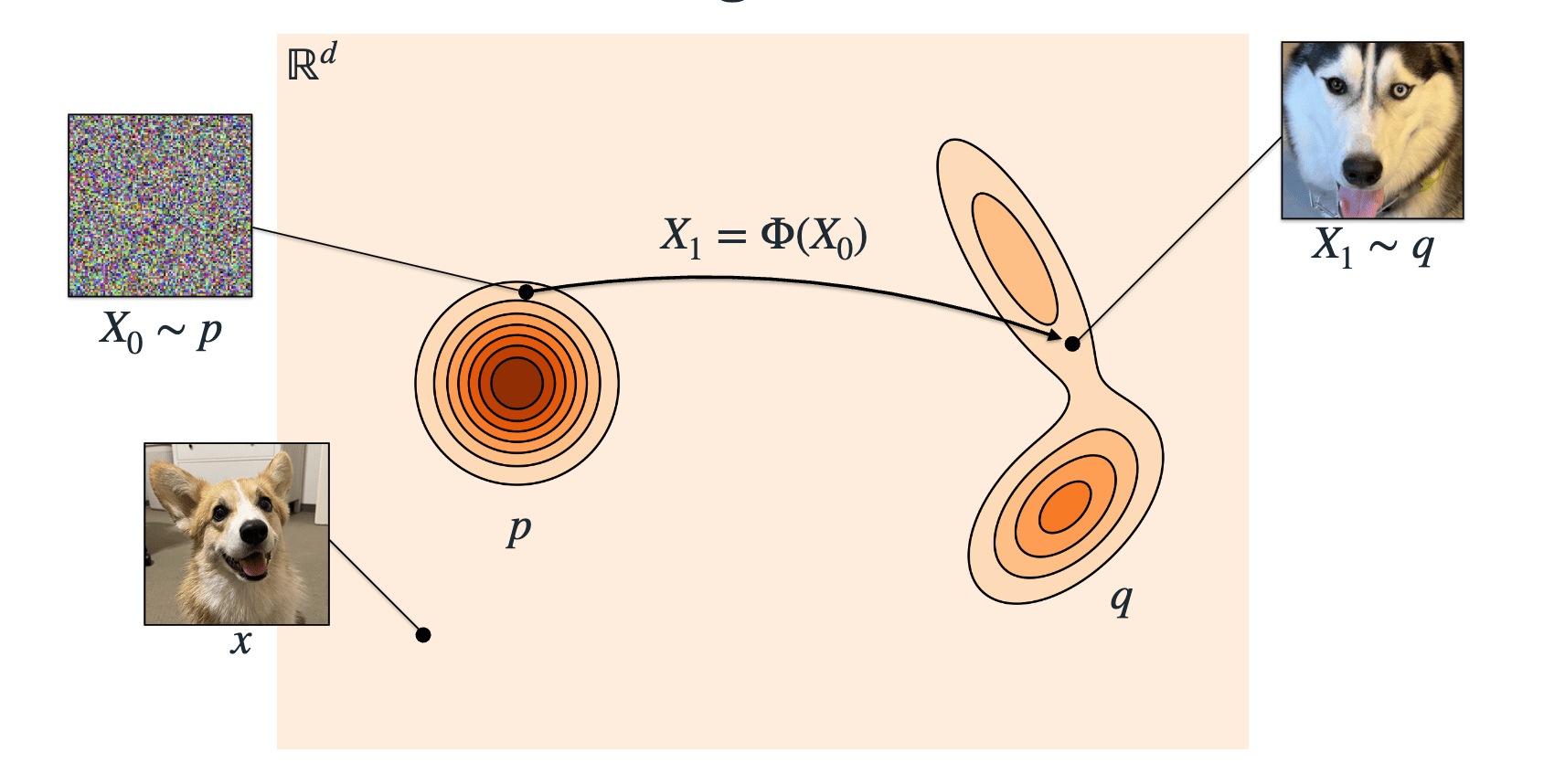

Flow-Matching

Easy to generate.

(Sample noisy interactions.)

Many manipulation trajectories and contact points

combinations are valid, but not all are useful.

Flow-Matching

We cannot

sample from this!

We know how to

sample from this!

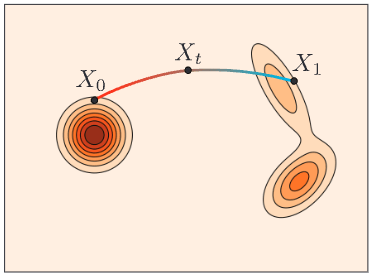

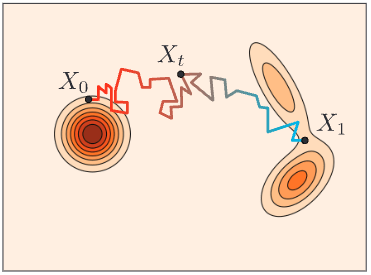

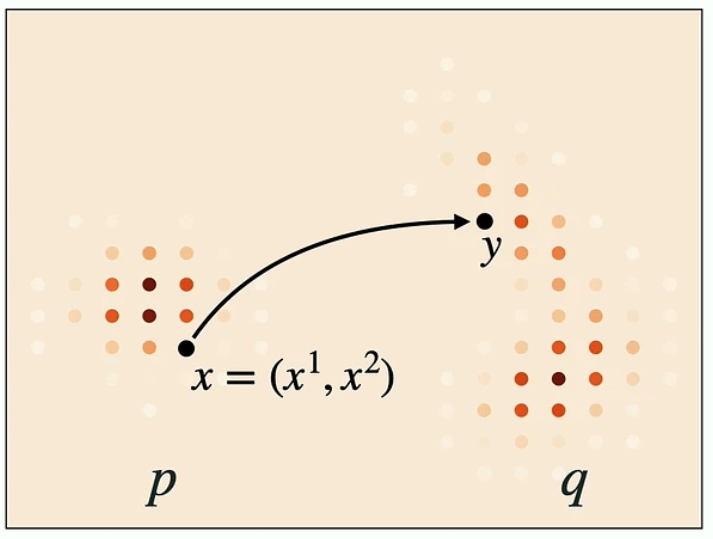

Flow-matching generates new samples from noise by learning a velocity field and integrating it.

Flow-Matching

\(\Phi(^0\mathcal{T})\)

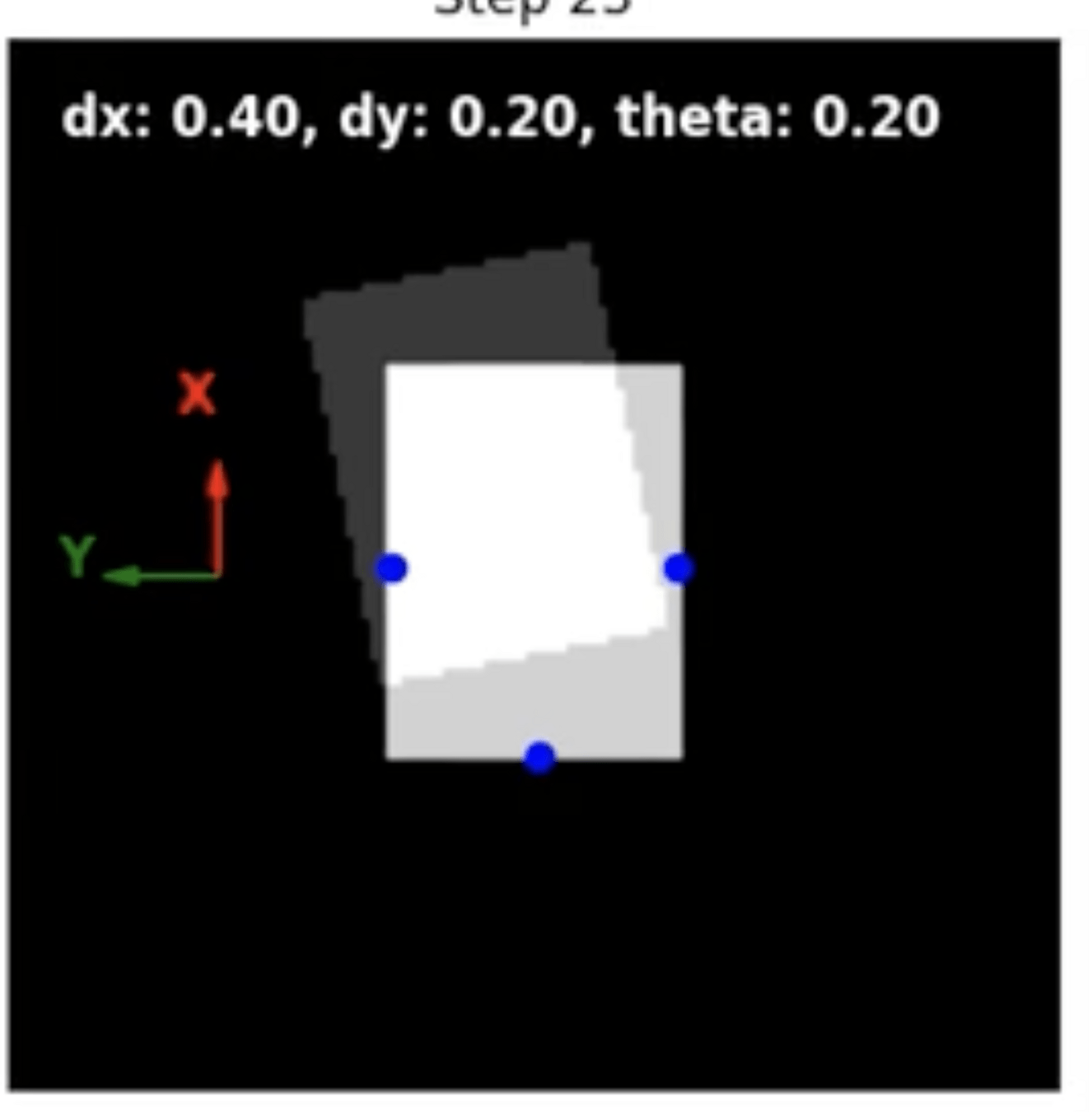

Flow Matching for Contact Modeling

We can learn contacts and manipulation trajectories with "vanilla" flow matching.

-

State space: \(B\)-robot trajectories of \(H\) steps, s.t.,

\[\mathcal{T} \in \mathbb{R}^{B \times H \times 2}\] -

Generation: learn velocity field \(u^\theta_t(\mathcal{T})\) from data, generate new trajectories by

- Sampling \(^0\mathcal{T} \sim \mathcal{N}(\bm{0}, \bm{I})\)

- Integrating: \(^{t+\Delta t}\mathcal{T} \gets ^t\mathcal{T} + u_t^\theta( ^t\mathcal{T}) \cdot \Delta t\)

Flow-Matching

\(\Phi(^0\mathcal{T})\)

This was not very stable.

Flow Matching for Contact Modeling

We can learn contacts and manipulation trajectories with flow matching.

- Let our state space be the space of \(B\)-robot trajectories of \(H\) steps, s.t.,

\[\mathcal{T} \in \mathbb{R}^{B \times H \times 2}\]

- Once learning a velocity field \(u^\theta_t(\mathcal{T})\) from data, we can generate new trajectories by integrating: \[^{t+\Delta t}\mathcal{T} \gets ^t\mathcal{T} + u_t^\theta( ^t\mathcal{T}) \cdot \Delta t\]

Dataset of \(\langle O, T, \mathcal{K}, \mathcal{T} \rangle\)

Initial Contact

Points

Manipulation

Trajectories

Transform

Observation

Flow Matching for Contact Modeling

We can learn contacts and manipulation trajectories with flow matching.

- Let our state space be the space of \(B\)-robot trajectories of \(H\) steps, s.t.,

\[\mathcal{T} \in \mathbb{R}^{B \times H \times 2}\]

- Once learning a velocity field \(u^\theta_t(\mathcal{T})\) from data, we can generate new trajectories by integrating: \[^{t+\Delta t}\mathcal{T} \gets ^t\mathcal{T} + u_t^\theta( ^t\mathcal{T}) \cdot \Delta t\]

Continuous flow matching for contact modeling.

Continuous flow matching for contact modeling.

Continuous flow-matching was unstable.

Flow Matching for Contact Modeling

Solution:

Split the representation, but generate concurrently.

Continuous flow matching.

Contact Points

\[\mathcal{K} \in \mathbb{R}^{B \times 2}\]

Manipulation Trajectories

\[\mathcal{T} \in \mathbb{R}^{B \times H \times 2}\]

(always rooted at the origin)

Learn two velocity fields, \(u^{\theta}_{\mathcal{K},t}( ^t\mathcal{K})\) and \(u^{\theta}_{\mathcal{T},t}( ^t\mathcal{T})\), and concurrently generate both contact points and manipulation trajectories:

\[^{t+\Delta t}\mathcal{K} \gets ^t\mathcal{K} + u_{\mathcal{K},t}^\theta( ^t\mathcal{K}) \cdot \Delta t\] \[^{t+\Delta t}\mathcal{T} \gets ^t\mathcal{T} + u_{\mathcal{T},t}^\theta( ^t\mathcal{T}) \cdot \Delta t\]

Continuous-Continuous.

Continuous flow-matching co-generation was better, but still unstable.

We fundamentally have two decisions to make:

- Where to make contact

- How to move.

Flow Matching Co-Generation for Contact Modeling

We fundamentally have two decisions to make:

- Where to make contact

- How to move.

We fundamentally have two decisions to make here:

- Where to make contact

- How to move.

Flow Matching Co-Generation for Contact Modeling

Noisy

Noisy

Clean

Clean

We fundamentally have two decisions to make here:

- Where to make contact

- How to move.

Flow Matching Co-Generation for Contact Modeling

We fundamentally have two decisions to make here:

- Where to make contact

- How to move.

\(u^\theta_\text{dis}\)

\(u^\phi_\text{cont}\)

Flow Matching Co-Generation for Contact Modeling

Generate continuous manipulation trajectories.

We fundamentally have two decisions to make here:

- Where to make contact

- How to move.

\(u^\theta_\text{dis}\)

\(u^\phi_\text{cont}\)

Tie contact points to the

discrete observation-space.

Generate continuous manipulation trajectories.

Flow Matching Co-Generation for Contact Modeling

Contact Point Generation

We can pose this as a discrete problem, asking

which pixels in our image observation should be used for contact points?

Discrete Flow Matching

Flow

Diffusion

Discrete Flow

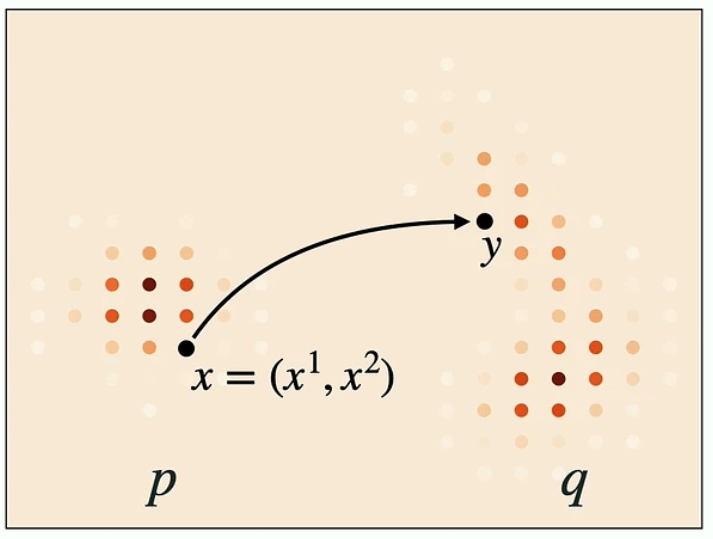

Discrete Flow Matching

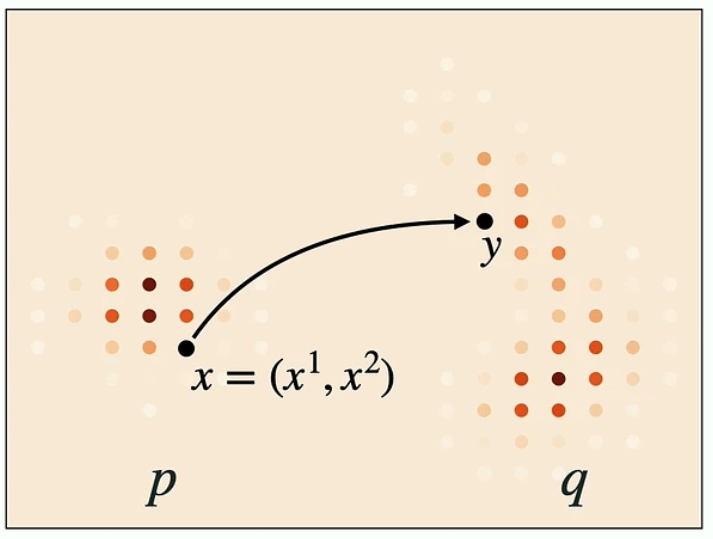

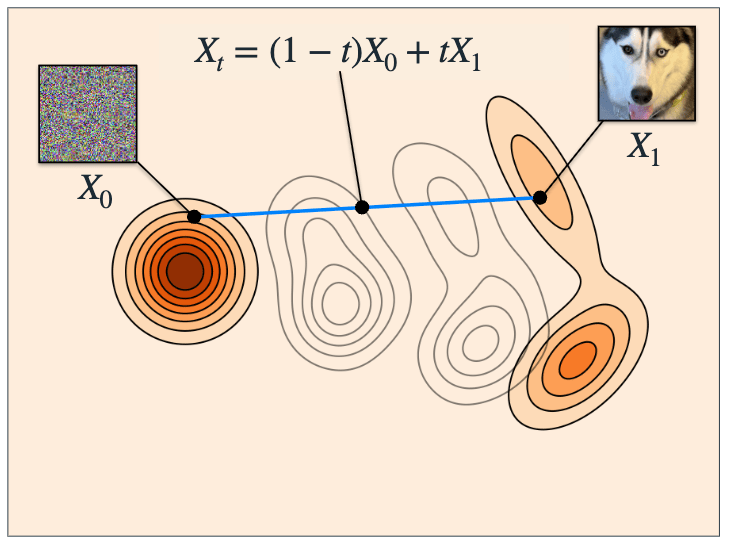

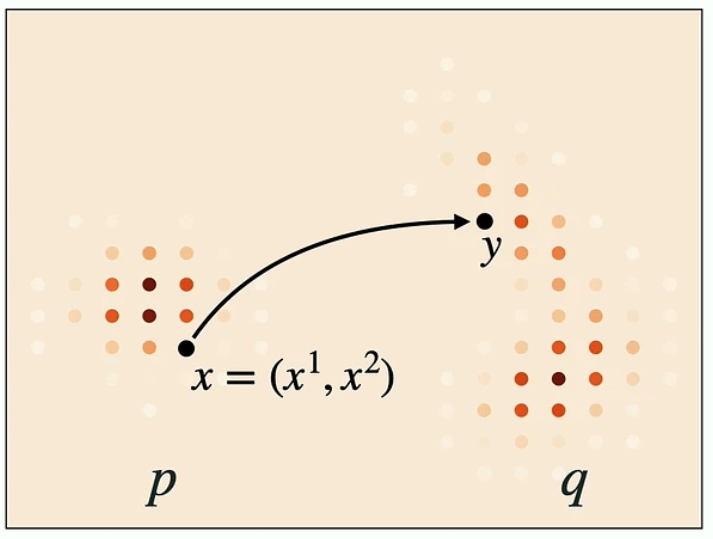

Let's look at this 2D state space for example:

- State space of token sequences \(\mathcal{S} = \mathscr{T}^d\).

- In our case \(d=2\), and a state is \(x = (x^1, x^2)\).

As before, we require two components:

- A velocity field \(u_t(y,x)\), and

- An initial value \(X_0\).

Getting an initial value is easy. We could

- Sample each token uniformly over the vocabulary

- Set all to a "mask" value \(X_0 = (\texttt{[M]}, \texttt{[M]}, \cdots)\)

Discrete Flow Matching: Velocity Field

For the velocity field, things are a bit different in the discrete case.

For some state \(x=(x^1, x^2)\), we want

- The probability of \(x^1\) transitioning to \(X^1_1\) should be \(1\), and

- The probability of \(x^2\) transitioning to \(X_1^2\) should be \(1\).

That is, we could define a factorized velocity \(u^i(\cdot, x) = \delta_{X^i_1}\).

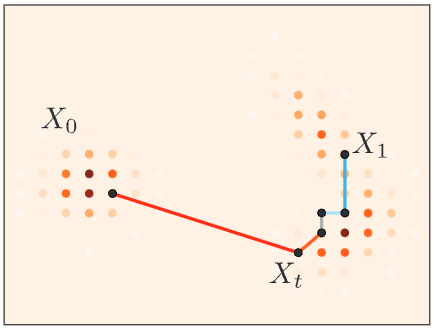

Discrete Flow Matching: Interpolation

In continuous flow matching, we asked a model to predict the velocity at some interpolated state \(x_t\).

Given \(X_0\) and \(X_1\), one way to obtain \(X_t\) in the discrete case is to have each element \(X_t^i\) as

- \(X_0^i\) with probability \((1-t)\)

- \(X_1^i\) with probability \(t\)

Discrete Flow Matching: Training

Similar to the continuous case

- Randomly choose \(X_0\) from the noise distribution \(p_0\) and \(X_1\) from the dataset.

- Sample \(t \sim U(0,1)\).

- Get \(X_t\) from "mixing" interpolation.

- Set target velocity \(u^i(\cdot, x) = \delta_{X^i_1}\).

- Supervise on the loss

\[ \mathcal{L}_\text{dis}:= \mathbb{E}_{t, X_1, X_t} \sum_{i} D_{X_t} \left( \dfrac{1}{1-t} \delta(\cdot, X_1^i), u_t^{\theta, i}(\cdot, X_t) \right) \\ \; \\ \theta^* = \arg \min_\theta \mathcal{L}_\text{dis}\]

Discrete Flow Matching: Generation

In essence, a similar process to the continuous case.

Starting with \(X_t = X_0\):

- Compute velocity (i.e., logits) \(u^\theta_t(\cdot, X_t)\)

- Obtain \(X_{t + \Delta t}\) by sampling from the categorical distribution defined by the logits \(u^\theta_t(\cdot, X_t)\)

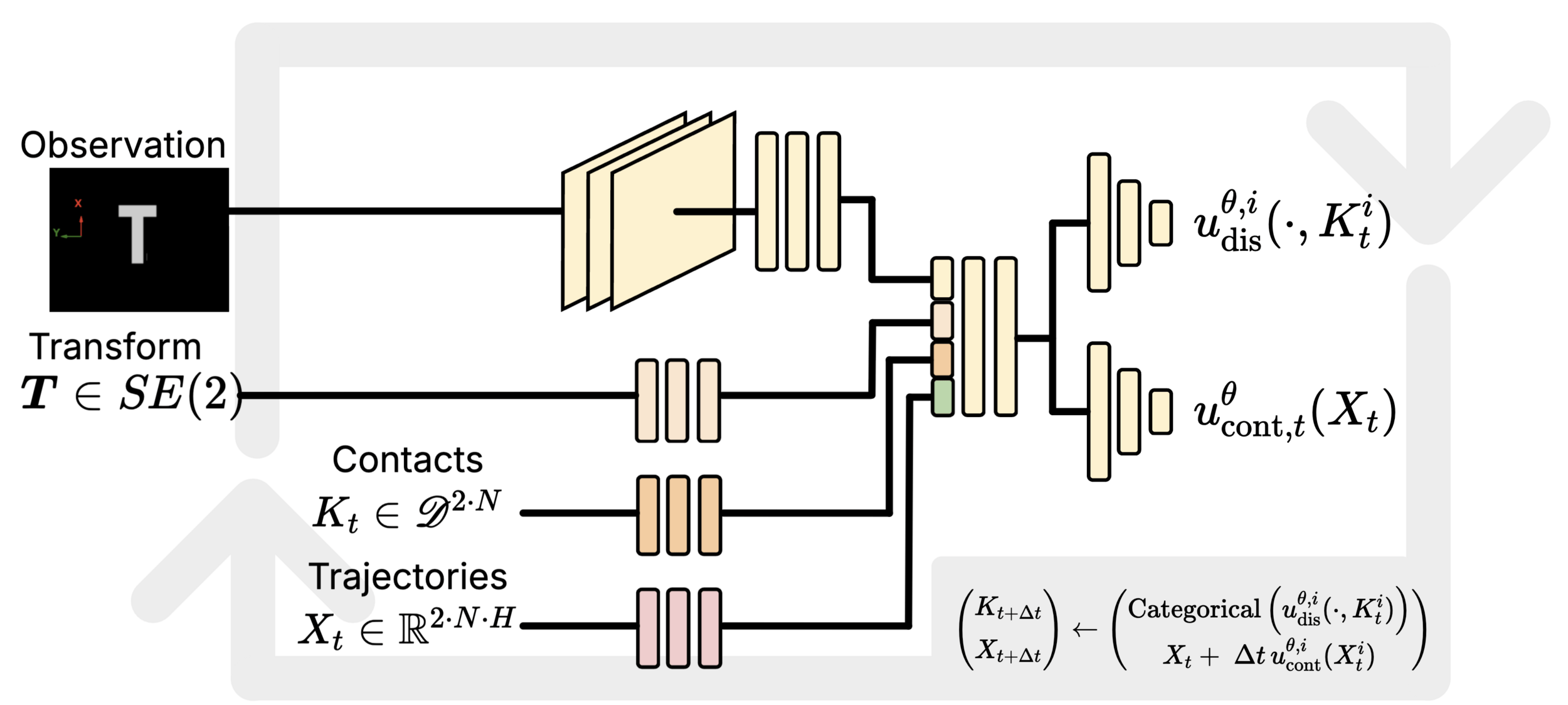

Flow Matching Co-Generation for Contact Modeling

- For flow-matching co-generation [1, 2], operates on two state spaces:

- Discrete contact points: \(K \in \mathscr{D}^{B \times 2}\)

- Continuous trajectories: \(\mathcal{T} \in \mathbb{R}^{B \times H \times 2}\)

- Concurrently learn two velocity fields:

- a continuous velocity field \(u^{\theta}_{\text{cont},t}(^t\mathcal{T})\),

- and "discrete velocity" \(u^{\theta, i}_{\text{dis},t}(\cdot, ^{t\!}K^i)\).

- (Factorized discrete logits.)

- And generate by:

- Sampling \(^0\mathcal{T} \sim \mathcal{N}(\bm{0}, \bm{I})\) and \(^0K := \{(\text{M},\text{M})\}^B\)

- Integrating

\(u^\theta_\text{dis}\)

\(u^\phi_\text{cont}\)

Flow Matching Co-Generation for Contact Modeling

- For flow-matching co-generation [1, 2], operates on two state spaces:

- Discrete contact points: \(K \in \mathscr{D}^{B \times 2}\)

- Continuous trajectories: \(\mathcal{T} \in \mathbb{R}^{B \times H \times 2}\)

- Concurrently learn two velocity fields:

- a continuous velocity field \(u^{\theta}_{\text{cont},t}(^t\mathcal{T})\),

- and "discrete velocity" \(u^{\theta, i}_{\text{dis},t}(\cdot, ^{t\!}K^i)\).

- (Factorized discrete logits.)

- And generate by:

- Sampling \(^0\mathcal{T} \sim \mathcal{N}(\bm{0}, \bm{I})\) and \(^0K := \{(\text{M},\text{M})\}^B\)

- Integrating

Flow Matching Co-Generation for Contact Modeling

- Discrete-contnuous flow-matching proved to be more robust than alternatives.

- Continuous-continuous flow matching followed,

- Continuous "naive" flow matching was least stable.

Observation

Transform

Contacts

\(K_t \in \mathscr{D}^{2\cdot N}\)

Trajectories

\(X_t \in \mathbb{R}^{2\cdot N \cdot H} \)

Flow Matching Co-Generation for Contact Modeling

Flow Matching Co-Generation for Contact Modeling

- For flow-matching co-generation [1, 2], operates on two state spaces:

- Discrete contact points: \(K \in \mathscr{D}^{B \times 2}\)

- Continuous trajectories: \(\mathcal{T} \in \mathbb{R}^{B \times H \times 2}\)

- Concurrently learn two velocity fields:

- a continuous velocity field \(u^{\theta}_{\text{cont},t}(^t\mathcal{T})\),

- and "discrete velocity" \(u^{\theta, i}_{\text{dis},t}(\cdot, ^{t\!}K^i)\).

- (Factorized discrete logits.)

- And generate by:

- Sampling \(^0\mathcal{T} \sim \mathcal{N}(\bm{0}, \bm{I})\) and \(^0K := \{(\text{M},\text{M})\}^B\)

- Integrating

The models flexibly select number of robots, given a budget.

Flow Matching Co-Generation for Contact Modeling

Let's assume, for a moment, that we know how to plan for robots and objects.

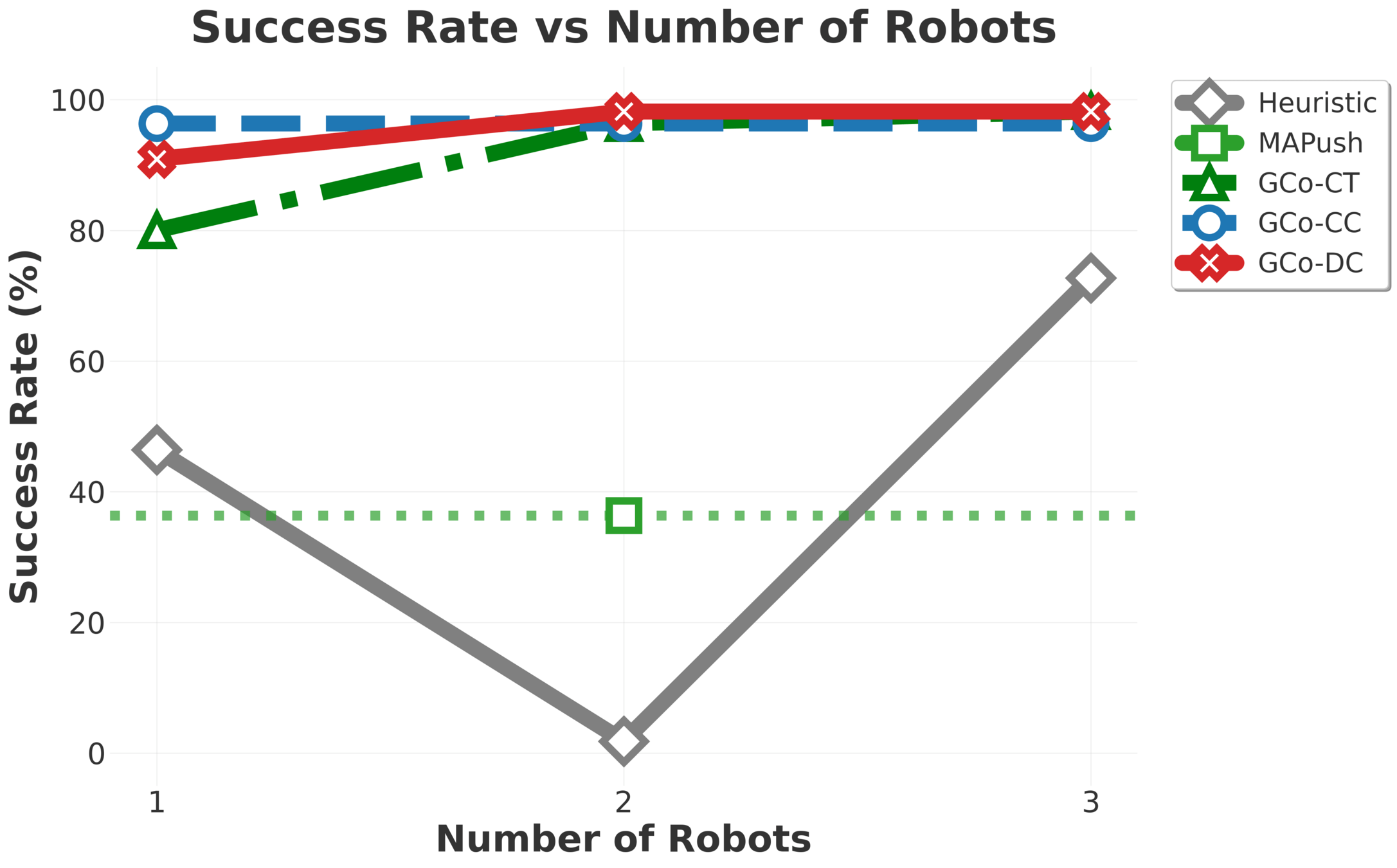

Collaborative Manipulation - Exprimental Evaluation

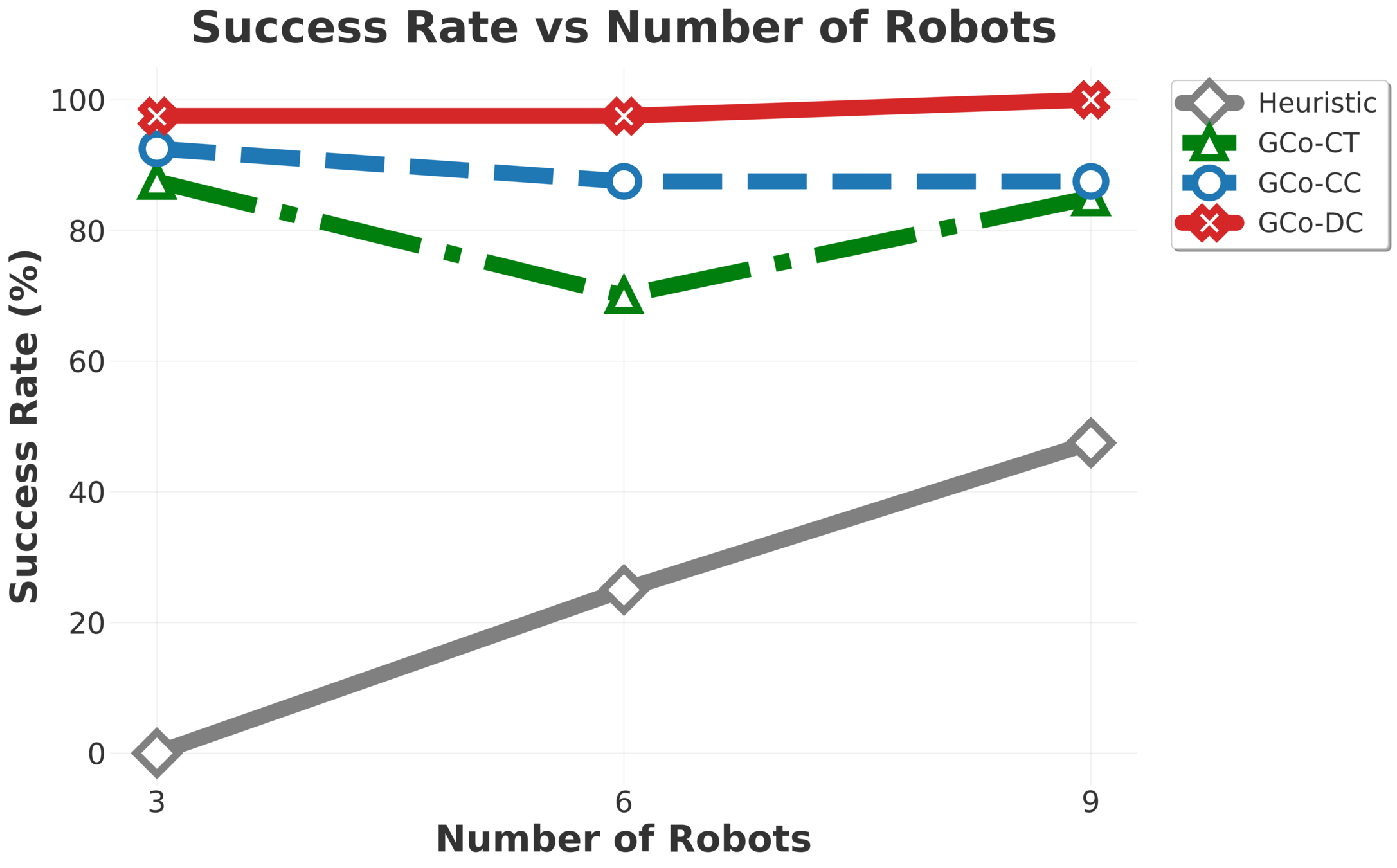

\(\text{GC}\scriptsize{\text{O}}\) composes per-object models, scaling to nine robots and five objects, including cases where objects outnumber robots.

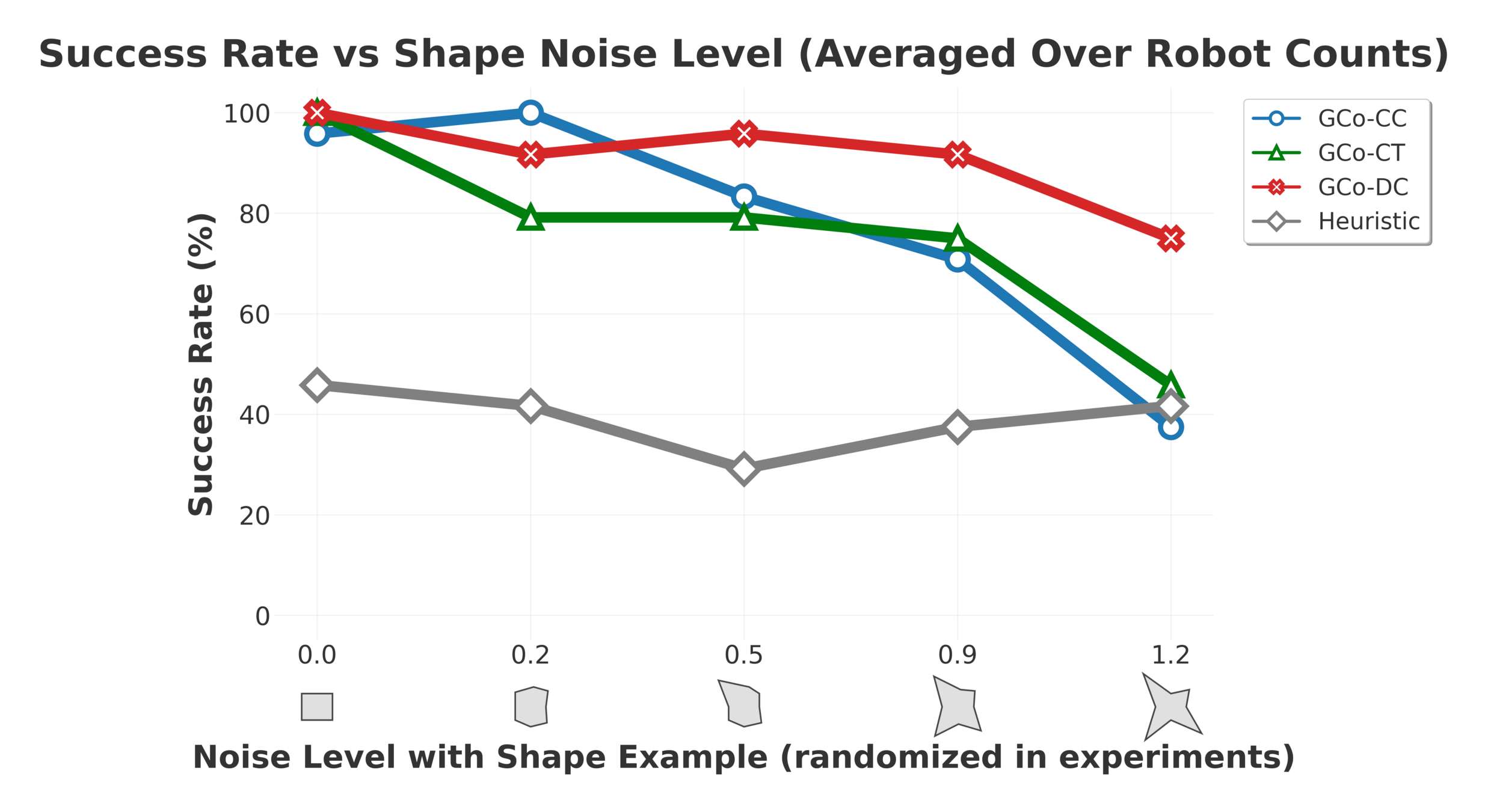

Collaborative Manipulation - Stress Testing

Despite being trained only on rectangles and circles, the models handle arbitrary polygons thanks to the flexibility in the observation medium

Collaborative Manipulation - Brief Results

Plots of single and multi

Agenda

- We'll start by looking at learning manipulation interactions,

- Continue to our multi-robot planning algorithm \(\text{G}\scriptsize{\text{SPI}}\),

Plan motions

to contact points

Learn short

push trajectories

Plan motions

for objects

Planning and Learning For Collaboration

Anonymous Multi-Robot Motion Planning

Object- and robot-planning fall under the same algorithmic umbrella.

- Given a set of goal configurations,

- Compute motions for all entities to

reach them.- Assignment is not fixed.

Plan compositions of short actions

Problem Formulation

Go from here to there (it does not matter who goes where).

Anonymous Multi-Robot Motion Planning

Minimizing

- Sum of costs or makespan (the time taken for all robots to arrive at goals).

- The computation time (overall or time-to-next-motion (if applicable)).

Anonymous motion planning has been explored in the Multi-Agent Path Finding (MAPF) community.

Some Background: TSWAP

kei18.github.io

Most algorithms, like TSWAP, operate on regular grids.

A few, like C-UNAV operate in the continuous space.

We take an intermediate approach, with motion-primitives.

Key ideas: swap goals between robots when it benefits the system.

Anonymous MAPF, traditionally, is solved on regular grids.

Some Background: Motion Primitives

Regular grid.

Motion primitives.

Swapping goals between robots when their next-best steps conflict with each other works... sometimes.

Other times it leads to deadlocks.

Naive Goal Swapping with Motion Primitives

Some Background: PIBT

An extremely scalable turn-by-turn procedure for labeled MAPF.

In a nutshell, high priority robots can push away lower priority ones.

Some Background: PIBT

An extremely scalable turn-by-turn procedure for labeled MAPF.

A single robot (loosely) operates as follows:

- Initialize a random priority \(\in [0,1]\) (without repetition with others).

Then, in the order of priorities:

- Choose next step in direction of goal.

- If step is occupied:

- The blocking robot inherits the priority of the acting robot.

- The blocking robot attempts to move away in a way that does not collide with the acting robot.

- Recursively called on blocking robots until a safe motion is found.

This is not only a continuous-space issue, actually. PIBT only guarantees reachability and not remaining at goals.

PIBT with Motion Primitives

Works... sometimes.

Anonymous Multi-Robot Motion Planning

What we want

Livelocks

Deadlocks

What we get

(from naively applying existing AMAPF ideas)

To mitigate these issues, we developed the "\(\text{G\scriptsize SPI}\)" algorithm, a "continuous-space" hybrid adaptation of PIBT with gaol-swapping inpired by TSWAP and C-UNAV.

Anonymous Multi-Robot Motion Planning

PIBT

+ Goal Swapping

= \(\text{G\scriptsize SPI}\) (Goal Swapping with Priority Inheritance)

In a nutshell:

Setup:

- Robots \(R^i\) assigned goals \(g^i\), and priorities \(\prec\) initialized.

Loop:

- For \(R^i, R^j\), if

- Swapping goals benefits higher priority \(R^i\) (\(R^i \prec R^j\)), and swapping goals benefits overall system cost:

- Swap goals and priorities.

- Swapping goals benefits higher priority \(R^i\) (\(R^i \prec R^j\)), and swapping goals benefits overall system cost:

- Each robot proposes best-next motion primitive.

- Robots \(R^i \prec R^j\) recursively reserve volumes.

\(\text{G\scriptsize SPI}\)

\(\text{G{\scriptsize SPI}}\)

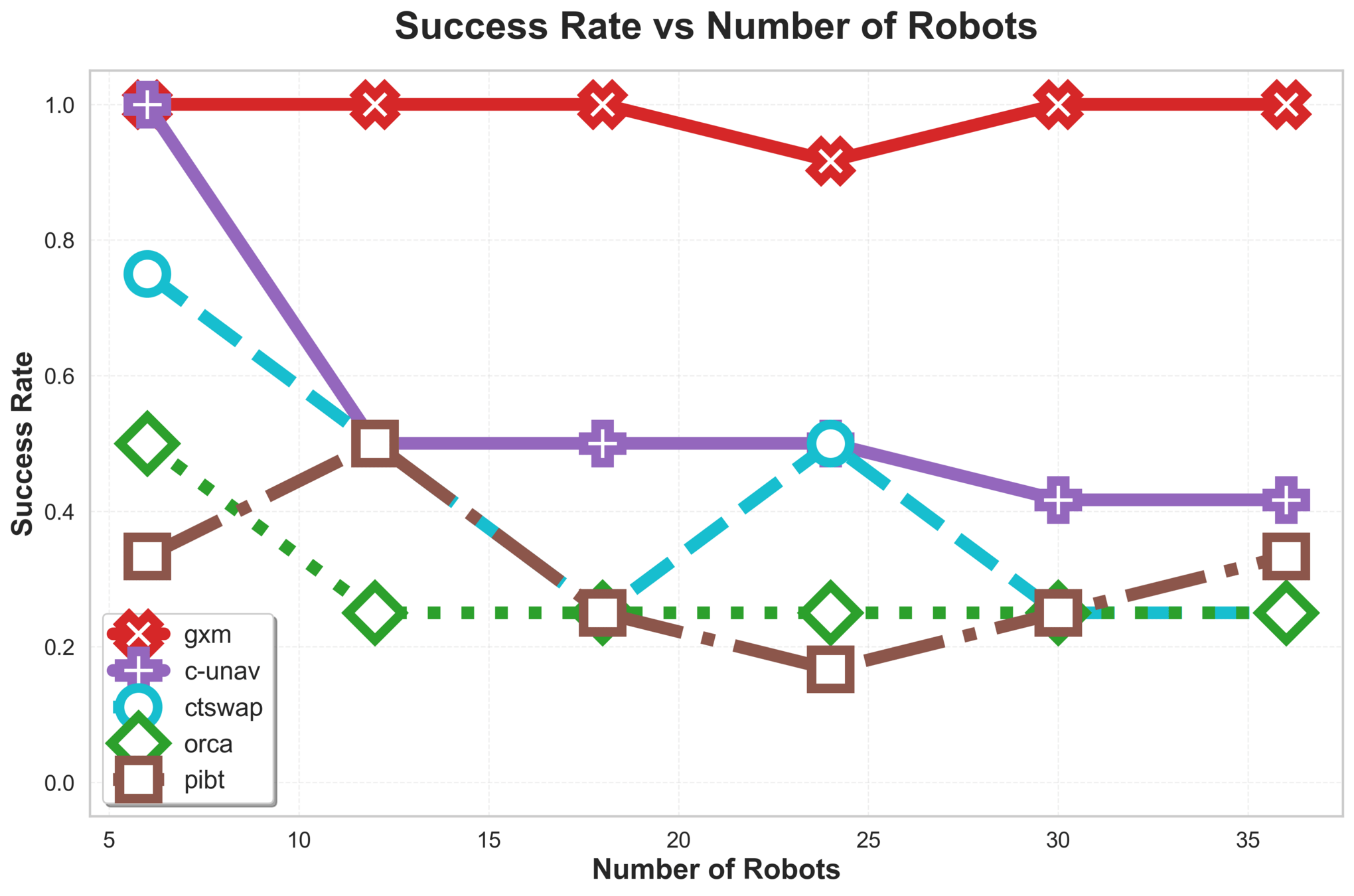

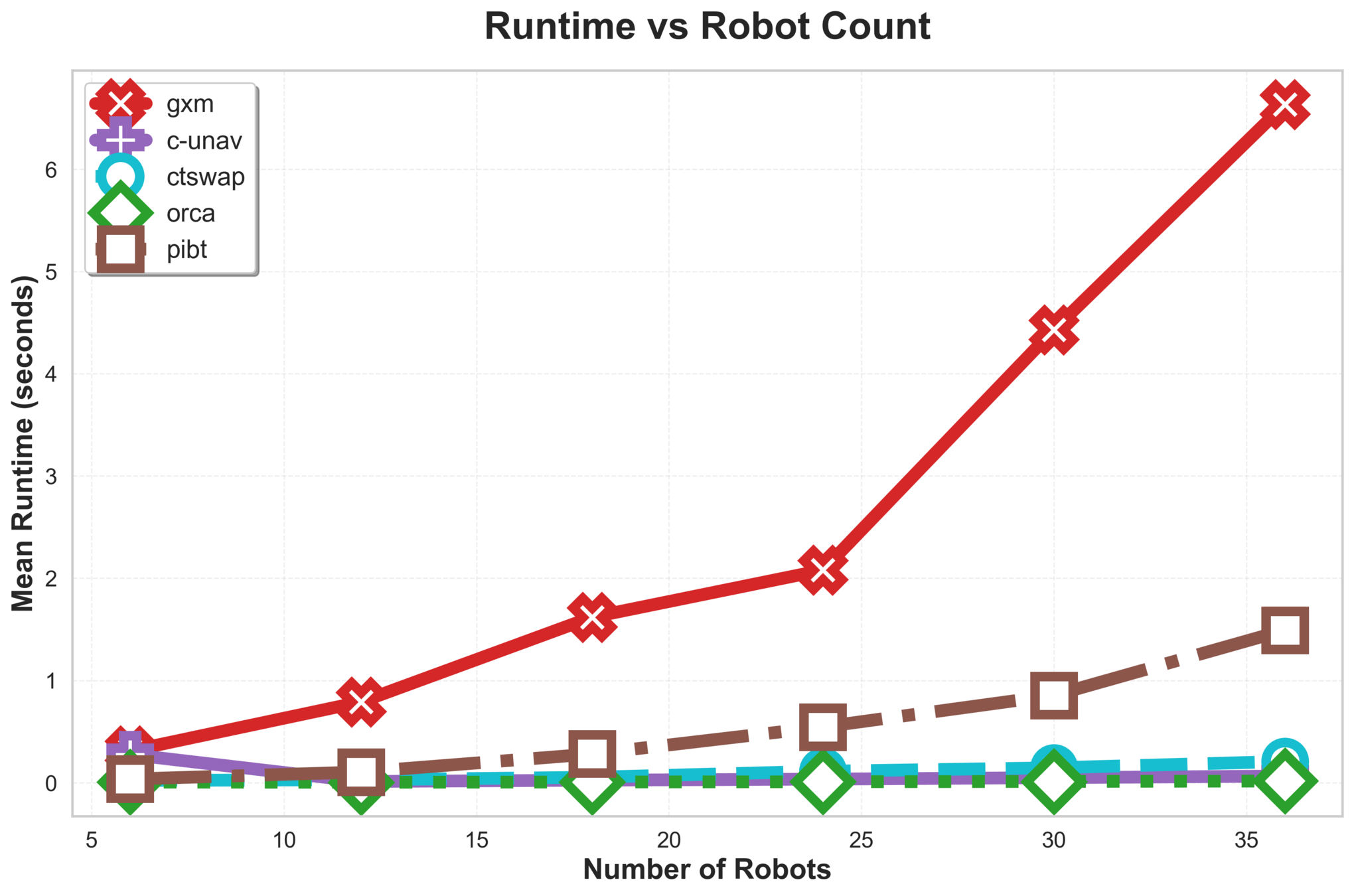

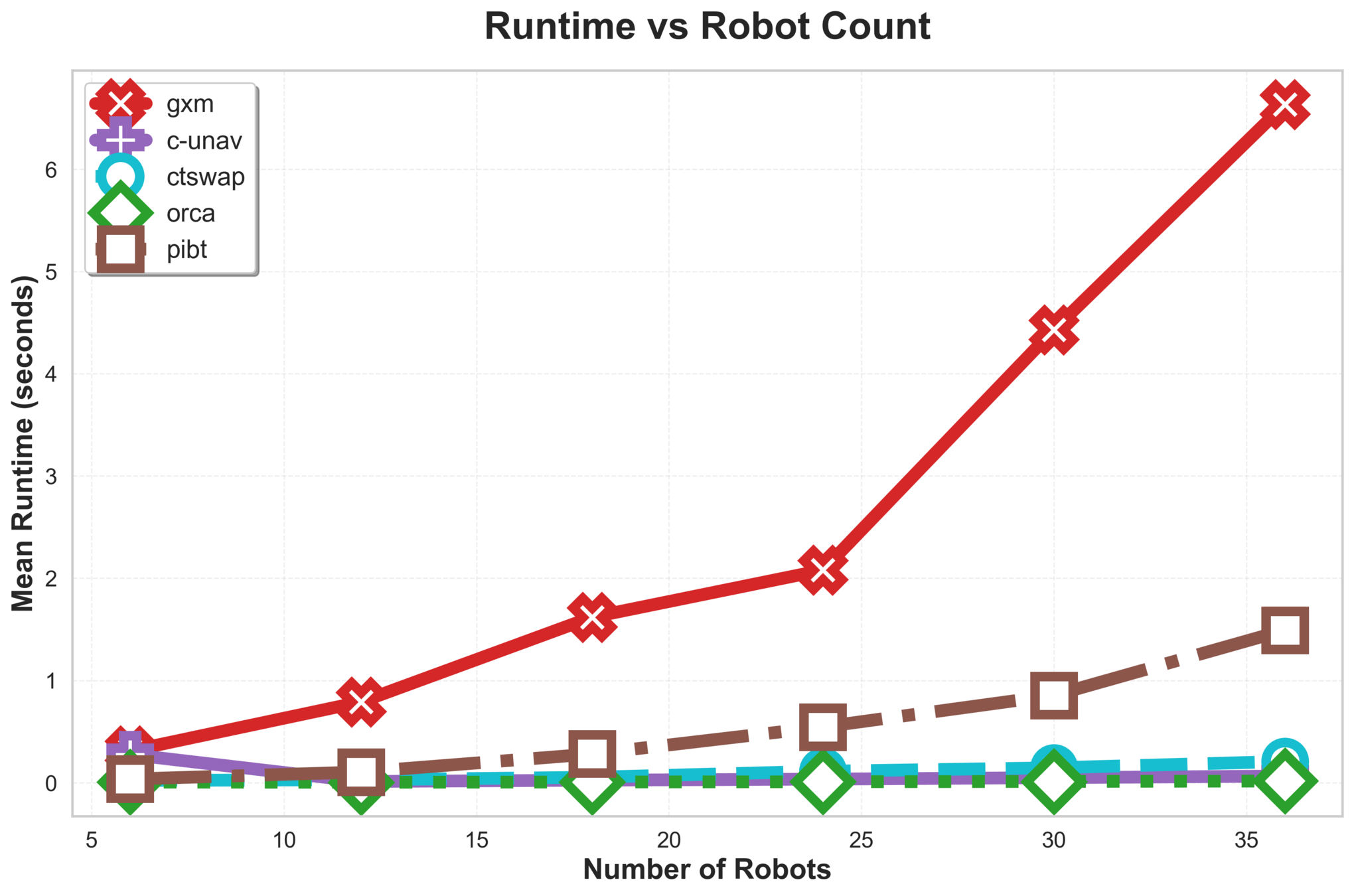

\(\text{{G\scriptsize SPI}}\) is efficient and scales to 300 robots in our experiments.

Straight lines are the result of effective goal swapping.

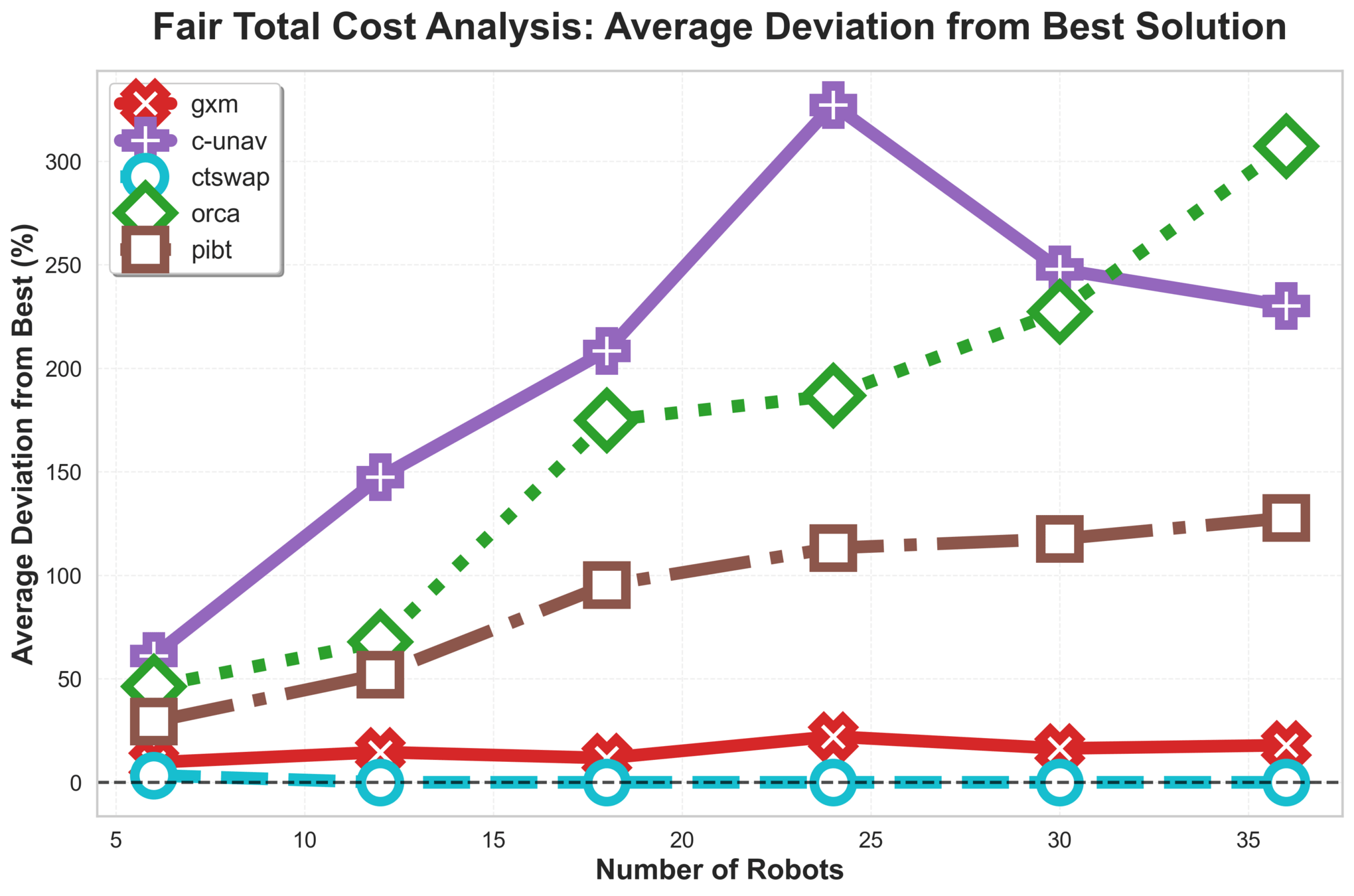

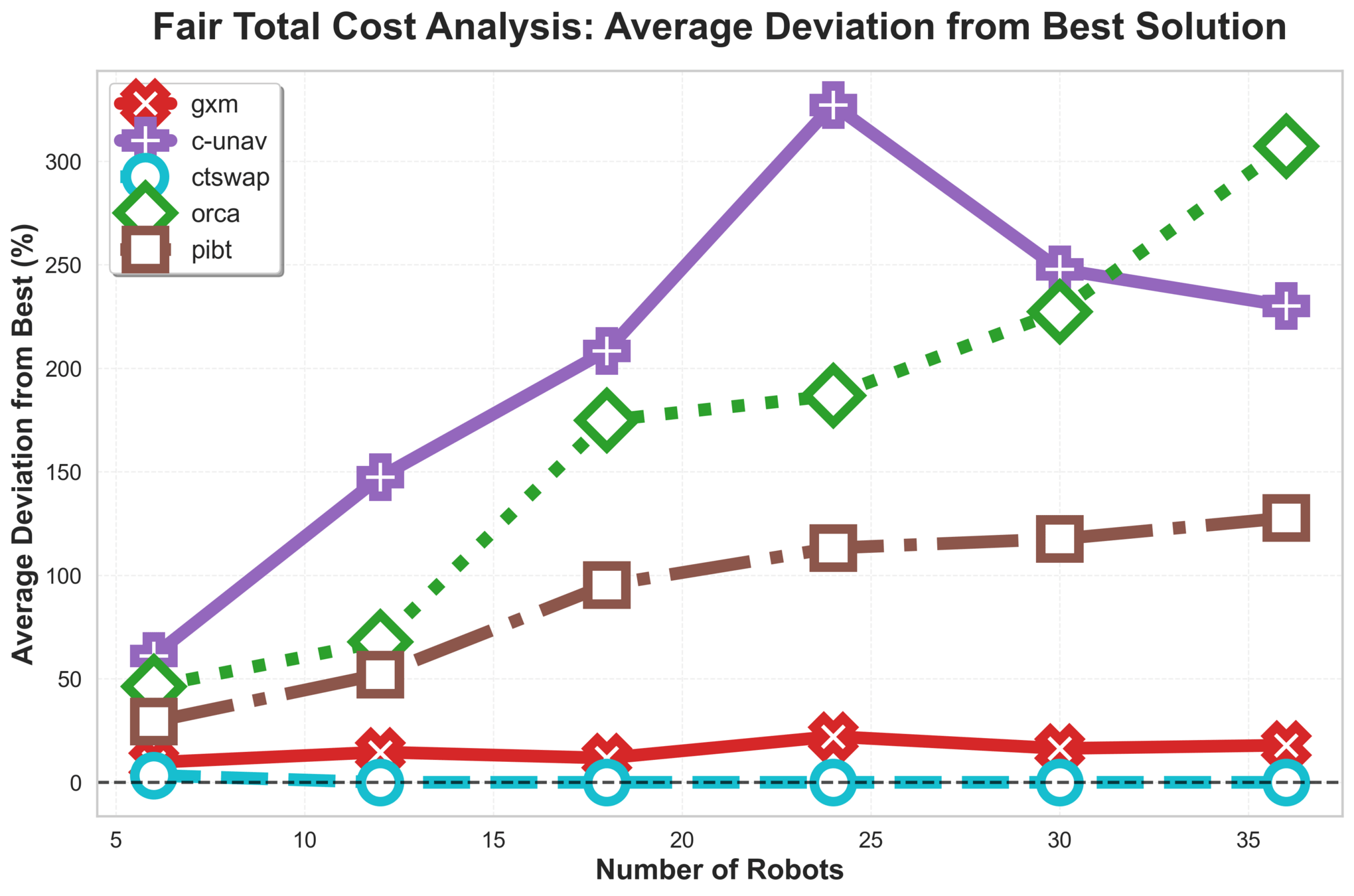

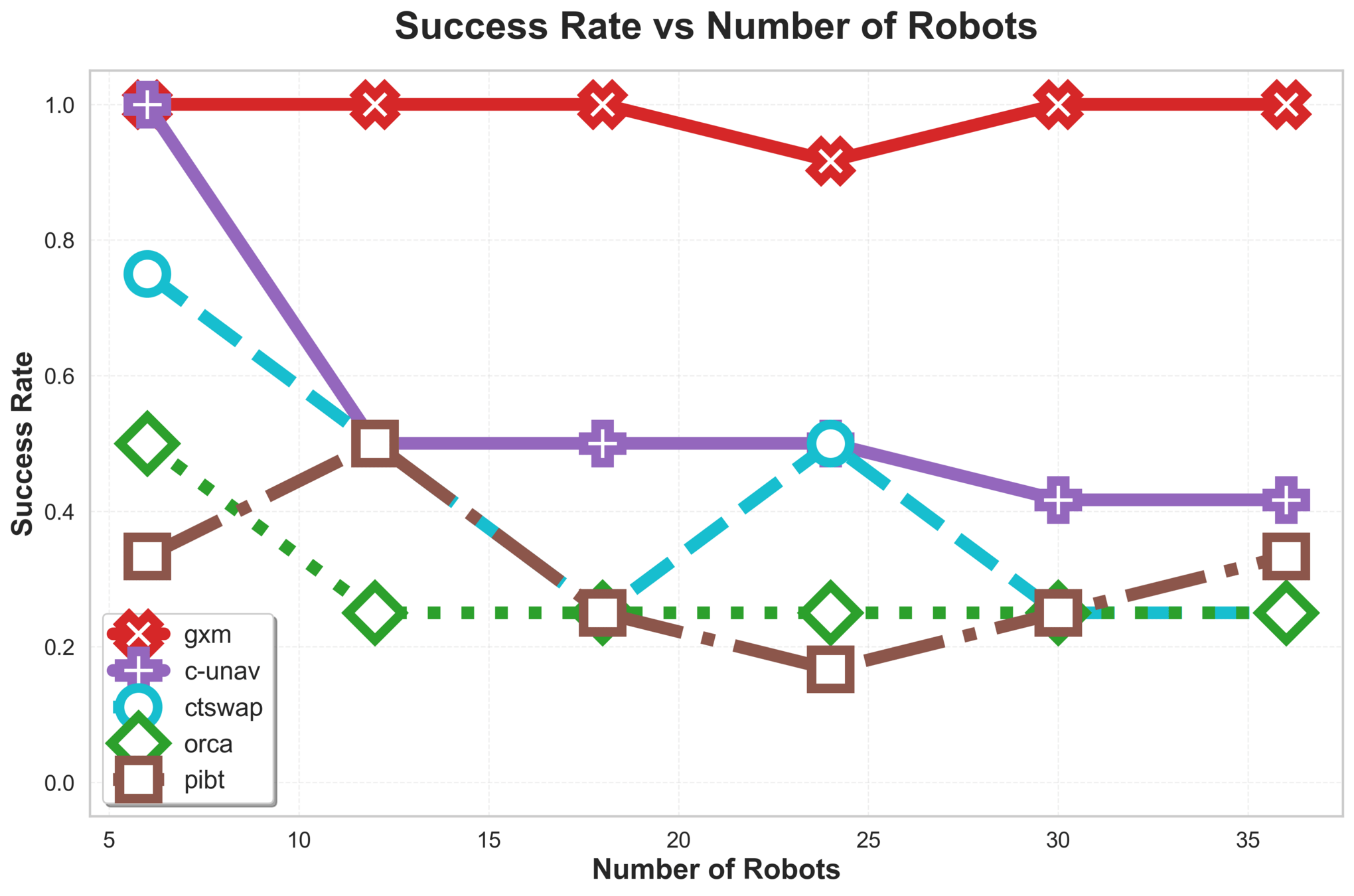

\(\text{G{\scriptsize SPI}}\) Analysis

\(\text{{G\scriptsize SPI}}\) handles stress tests that often break algorithms:

- Extremely tight spaces and "following" concurrent movements.

\(\text{G{\scriptsize SPI}}\) Analysis

Results

\(\text{G{\scriptsize SPI}}\) Analysis

Results

\(\text{G{\scriptsize SPI}}\) Analysis

C-UNAV / ORCA

Failure cases for baselines

PIBT

TSWAP

One Step-Manipulation

Move robots, manipulate a single object.

Composing Manipulation Policies with Planning

Observe objects, plan objects, generate manipulation interaction, plan robots, execute, repeat.

Agenda

- We'll start by looking at learning manipulation interactions,

- Continue to our multi-robot planning algorithm \(\text{G}\scriptsize{\text{SPI}}\),

Plan motions

to contact points

Learn short

push trajectories

Plan motions

for objects

Planning and Learning For Collaboration

Agenda

- We'll start by looking at learning manipulation interactions,

- Continue to our multi-robot planning algorithm \(\text{G}\scriptsize{\text{SPI}}\),

Plan motions

to contact points

Learn short

push trajectories

Plan motions

for objects

Planning and Learning For Collaboration

[AAAI-26 WoMAPF] GCo

By yorai

[AAAI-26 WoMAPF] GCo

- 5